In the past year, I’ve read two pieces—one a recent long blog post, the other a book—by talented authors detailing how their careers went to hell. (Then they resurrected their careers by writing about it, but never mind.)

These weren’t “the publishing industry is dying and nobody can make a living writing books anymore” sort of stories that seem to pop up every couple of days. Besides, even in the best of times, not many folks made a living writing.

These weren’t “the publishing industry is dying and nobody can make a living writing books anymore” sort of stories that seem to pop up every couple of days. Besides, even in the best of times, not many folks made a living writing.

No, these were by young successful authors, authors who got big honking advances from major publishing houses. Yet, in short order, they were flat freakin’ max-out-the-credit-cards broke on their butts.

In 2008, Emily Gould got a $200,000 advance for her essay collection, “And the Heart Says … Whatever.” It vanished astoundingly fast, she writes in a post for Debt Ridden titled How Much My Novel Cost Me:

Besides a couple of freelance writing assignments, my only source of income for more than a year had come from teaching yoga, for which I got paid $40 a class. In 2011 I made $7,000.

Blame “under-performing” book sales, taxes, absurdly high rents in Brooklyn (where she actually lived fairly affordably) and crippling health insurance costs (I’d bet the rent that few writers bitch about Obamacare). But also blame Gould, as she herself does. We’ll get to why in a moment.

Then there’s Benjamin Anastas. In 2012’s Too Good to be True, he details his rise as a promising young novelist—prestigious publishing house, generous advance—and fall, precipitated by poor sales and hastened along by an affair and divorce. Debt soon followed.

Here’s what Gould and Anastas have in common, beyond that rise and fall and attendant debt. For all practical purposes, after their initial successes, each stopped writing. Gould managed to persuade herself she was still writing, after a fashion:

For many years I have been spending a lot of time on the internet. In fact, I can’t really remember anything else I did in 2010. I tumbld, I tweeted, and I scrolled. This didn’t earn me any money but it felt like work. I justified my habits to myself in various ways. I was building my brand. Blogging was a creative act—even “curating” by reblogging someone else’s post was a creative act, if you squinted.

Anastas used his advance to help fund a year in Italy, where he could live cheaply while he and his wife both worked on their next books. She finished a draft of a book. He did not. Each morning, he’d open his laptop:

“…Trying to summon the right word, and then another, and then another after that, to fill the silence and the cursor would sit there blinking its eye at me, and I would feel my heart go cold with dread.”

He finally finished it, but his publisher didn’t bite. He “wrote” again in a rented house during a semester teaching at a college in Maryland:

I have put “wrote” in quotations marks because I didn’t actually manage to do much writing—instead, I rewrote everything I had started on the computer screen over and over until the spark of life had been extinguished and the paragraphs had a perfect, sculptural look. …Once I had toggled the piece I was working on to death, I would file it away in FALSE STARTS and upon up a new file in Word to begin the process all over again.

Let’s be clear about one thing. Am I insanely jealous of these two who, at a very young age, received huge advances from major publishers? Oh. Hell. Yeah.

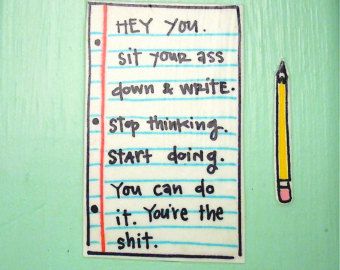

But I’m also teeth-grindingly frustrated by the scenario of any writer who squanders his or her gift by Not Writing. I’m in the midst a longstanding argument with a writer friend who insists she needs “inspiration” before she sits down at the computer. She—as, I suspect, with Gould and Anastas—doesn’t want to write anything unless it’s good from the get-go.

“Just sit down,” I say. “Type. At some point, the drek will get better.”

I’ve ranted about this before and I’ll probably rant again. And maybe these rants are solely a way of justifying my own habit of typing pages and pages of drek. Probably. But damn, it feels good to go back and shine that sucker up, to turn it into something I never realized it could be as I shielded my eyes from its original drek-ness. It’s like watching the teenage slacker you once feared would end up in a mug shot become a productive member of society, a child you’re proud to call your own.

Let’s turn to another writer who’s found great success. Neil Gaiman tells aspiring authors exactly how to to get published

“How do you do it? You do it.

“You write.

“You finish what you write.”

Second the motion.

I, too, endorse the “just write” course of action. I wonder if this is where we’re blessed by our former career. I never had a good excuse not to write. I can’t say that imminent deadlines taught me a lot about how to structure fiction, but it sure taught me how to stop my bitching, sit down, and get the job done.

Now, I’ll qualify that by saying that I do have periods where I’m not actively setting down words. But I’m thinking about stories, always. I’m working out scenarios. I’m imagining characters. I’d liken it to training camp for a professional athlete. I’m getting my mind right for the challenges ahead.

As for the envy, it’s human nature, I’m afraid. It’s helpful to me to remember that novel writing isn’t a world of haves and have-nots. It’s a massive layer cake, with each layer having a little more than the layer immediately below it. Just as there are levels of success I hope to reach, I know I’m standing in a place where someone else wishes to climb. Thinking of that helps with the gratitude piece, being happy for what I’ve done and mindful of what I still hope to do—and being willing to lend a hand to someone else if I can.

What a thoughtful post, Craig. I like the concept of the layer cake – and of being mindful that it’s a privilege to be on any of the layers, and that there’s a responsibility to help others climb on up.